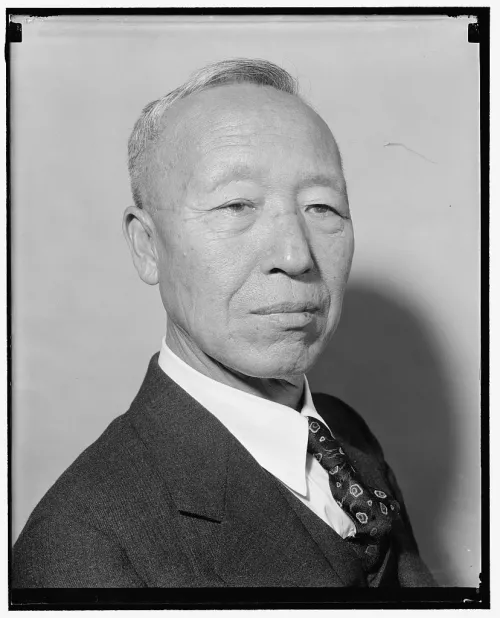

Syngman Rhee, the first president of South Korea, was born in 1875, completed a traditional classical education fitting his noble family heritage, and then entered a Methodist school where he learned English. He became an ardent nationalist and ultimately a Christian; in 1896, he joined with other Korean leaders to form the Independence Club, a group dedicated to Korean independence. When pro-Japanese elements destroyed the club in 1898, Rhee was arrested and imprisoned until 1904. Upon his release, he went to the United States, where in 1910, he received a Ph.D. from Princeton — the first Korean to earn a doctorate. He returned home in 1910, the same year Korea was annexed by Japan. He spent the next 30 years as a spokesman for Korean independence, and in 1919 was elected president of the "Korean Provisional Government" in exile in Washington, D.C. Rhee became the best known Korean leader during World War II and campaigned vigorously for a policy of immediate independence and unification of the Korean Peninsula. He soon built up a mass political organization supported by strong-arm squads. With the assassination of major moderate leaders, Rhee's new party won South Korea's first elections, and he became president in 1948. But political instability and ominous signals from Kim Il Sung's regime in North Korea had made the whole Korean Peninsula a tinderbox of the Cold War.

North Korean Invasion

On June 25, 1950, North Korea launched an overwhelming and sudden attack across the 38th parallel. The understrength and poorly equipped ROK Army, trained primarily for anti-guerrilla operations, was forced to retreat. The United Nations quickly resolved to give military support to the Republic of Korea, and a United Nations Command (UNC) was established. Troops from 15 countries—including the United States, Great Britain, France, Canada, Australia, the Philippines and Turkey—arrived in Korea to fight side by side with the ROK Army under the United Nations flag.

From Taejon, where Rhee's government had fled in the face of communist infantrymen and tanks, South Koreans were exhorted by their leaders to drive out the invaders, but to no avail. Seoul fell on June 28, and South Korean troops straggled in retreat across the Han River bridges. Those members of Rhee's government who had reached Taejon soon moved to Pusan, but after a week they relocated to Taegu to stay closer to the front. Rhee initially had vehemently resisted the advice of his aides and the American ambassador to relocate the government to Pusan, preferring to meet death at the hands of the enemy rather than to lead a government in exile. If he was to die, he had declared, it would be on the soil of his native land. Rhee later recanted once he came to realize the grave political implications should he fall into the hands of the North Koreans. One thing was certain: The invasion had brought a respite in Rhee's political wars; politics were put aside, if only for as long as it took to ascertain the South's ability to retain a toehold on the Korean Peninsula, along the Pusan Perimeter.

Meanwhile, in Tokyo, General Douglas MacArthur decided on a bold stroke: an amphibious landing at Inchon, about 18 miles west of Seoul, followed by a two-pronged attack against the communist armies in southern Korea. The success of the Inchon landing on Sept. 15–16, ushered in a new phase of the war. Following the retaking of Seoul by the UNC X Corps on Sept. 28, MacArthur and Rhee made a triumphal entry, driving by motorcade to the gutted capitol building. Rhee sensed victory within his grasp, and he lobbied for an all-out drive to annihilate the North Korean armed forces and liberate the communist North. On Oct. 7, the U.N. General Assembly approved a resolution permitting punitive action against North Korea and calling for the unification of the Peninsula. With shouts of "On to the Yalu," ROK troops poured across the 38th parallel. To the aged Rhee, a lifelong objective appeared in sight.

Rhee Seeks to Unify Korea

Rhee moved to capitalize on the U.N. advance across the parallel. As president, he believed it fell to him to appoint provisional governors in the Republic of Korea; he now began also to appoint governors to rule in his name over liberated areas of the North. But the United Nations ruled that his government had no authority north of the 38th parallel, and the General Assembly decreed that the government of a united Korea should be determined by U.N.-supervised elections throughout the country. Rhee bitterly opposed this ruling on the grounds that the legitimacy of the Republic of Korea had already been certified by a U.N. commission in 1948. Liberated areas of North Korea were nonetheless kept under military administration in accordance with the U.N. directive.

Early in the war, Rhee effectively gave Truman an ultimatum. Much as he might wish that Truman would accept his views and make American policy coincide with Korean policy, Rhee intended to pursue what he felt the welfare of his country demanded. Rhee declared: "The government and people of the Republic of Korea consider this is the time to unify Korea, and for anything less than unification to come out of these great sacrifices of Koreans and their powerful allies would be unthinkable. The Korean government would consider as without binding effect any future agreement or understanding made regarding Korea by other states without the consent and approval of the government of the Republic of Korea."

Catastrophe confronted Rhee and his government in November when thousands of communist Chinese troops eviscerated four South Korean divisions near the Chongchon River, and again in November when Chinese forces repulsed a new U.N. offensive. The ominous shadows threatening Seoul on Christmas 1950, finally enveloped the ravaged city as the new year dawned, and on Jan. 4, 1951, communist forces once again occupied the South Korean capital. As both MacArthur and Rhee noted, it was a new war.

As early as January 1951, Rhee was developing long-range plans for establishment of a Korean–American Society—an idea he hoped would produce major results in building friendship and understanding. Looking beyond the war to measures needed to ensure future security, Rhee noted that Korea's "national existence depends partly on international agreement for common security, and partly on our own military preparations, so that no neighbor can be tempted to make Korea an easy prey." But his political clashes with Truman gradually became more personal in nature, until a wedge had been firmly driven between the two wartime allies. Enmity as much as cooperation would soon characterize the relationship between the Truman and Rhee administrations, and hopes for warmer U.S.–ROK relations remained pinned to Truman's perceptions of U.S. security interests in East Asia.

Rhee's Presidency Threatened

As a war of stalemate dragged on through the spring and summer of 1951, Rhee's political wars heated up. With his term as president due to expire soon, Rhee's opponents—who dominated the National Assembly—were determined to overthrow him in the 1952 election, and they found many instances of corruption and malfeasance with which to attack the administration. One such scandal which threatened to undo Rhee involved the National Defense Corps (N.D.C.). The N.D.C. had been an amalgamation of various strong-arm "youth groups" which had been organized as a military unit just before the war. But when the corps actually had to be activated for combat, certain disturbing facts came to light. Those survivors who straggled south in the second evacuation of Seoul were in rags, and many suffered from extreme malnutrition. They brought back stories of nonexistent supplies and leadership. An investigation later revealed that the N.D.C. commander, a son-in-law of Rhee's defense minister, had embezzled funds allocated for the N.D.C.'s food, clothing and equipment—including rifles and ammunition.

Another scandal which rocked the Rhee administration was the Kochang massacre. In the course of an anti-guerrilla campaign in February 1951, a ROK Army detachment lost contact with a group of guerrillas near the village of Kochang. Furious, the South Korean commander accused the villagers of harboring the fugitives. After herding the inhabitants into a schoolyard, he ordered all 200 of the men of the village shot. Attempts by the National Assembly to investigate stories of the massacre were thwarted by Colonel "Tiger" Kim, a favorite of Rhee's whom the president later appointed director of the national police.

In his campaign to secure re-election, Rhee had two basic alternatives. One was to operate within the existing constitutional structure under which the president was elected by the Assembly, but to bring such pressure to bear on the legislature that it would be forced to accept him for a second term. Such a course relied heavily on Rhee's control of the Army and the vulnerability of many opposition legislators to bribes. But it in no way checked the constitutional prerogatives of the assembly. In the end, Rhee determined on a frontal assault against the Assembly, one which would neutralize it as a rival to the executive. In a series of speeches in the spring of 1952, Rhee equated his enemies in the assembly with the enemy in the communist North: both were out to destroy him, and thus to destroy free Korea. Rhee's cronies organized "spontaneous" demonstrations calling for the re-election of Rhee and for the selection of Lee Bum-suk, the new home minister, as his running mate.

On May 25, Rhee and Lee re-imposed martial law in Pusan, ostensibly as an anti-guerrilla measure. When the Assembly voted 96 to 3 (with numerous abstentions) to lift martial law, Rhee ordered the arrest of 47 assemblymen by ROK Army police and announced that "far-reaching communist connections have been uncovered, and authorities are taking steps to make a thorough investigation." He continued to wield the powers of his office as though the legislature did not exist. The political war between the president and the Assembly escalated, with more arrests of assemblymen and more charges of a communist conspiracy to depose Rhee and bring about unification negotiations with Kim II Sung's North Korean regime. While continuing to insist publicly that he was not a candidate for re-election, he flayed the National Assembly for having "betrayed the will of the people" and began to orchestrate his final maneuver against the assembly.

By June 23, 1952, Rhee had broken his opponents in the assembly, many of whom remained in hiding to avoid political arrest. By a vote of 61 to 0, the National Assembly extended Rhee in office "until the dispute is resolved," which, of course, was past the date of the scheduled election. Rhee's idea of resolving the crisis was to stage an assassination attempt against himself, whip up anti-communist hysteria, and — making full use of the strong-arm tactics of Lee Bum-suk and martial law commander Won Yong-duk — to browbeat the assembly. Finally, on July 5, with the entire assembly under virtual house arrest, by a vote of 163 to 0 (with 3 abstentions), it amended the constitution to allow for popular election of the president and for an upper house. Once his amendments were passed, Rhee's re-election was a foregone conclusion.

Rhee Attacks Peace Proceedings

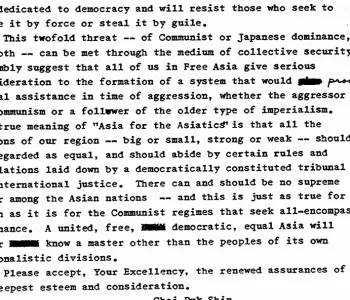

In April 1953, Rhee calculated how best to use his considerable influence to block an armistice which now seemed close. The ROK ambassador in Washington informed the United States that South Korea would withdraw its forces from the U.N. Command if the allies agreed to any armistice which permitted Chinese communist troops to remain on Korean soil. Within a month, the U.S. had countered by offering an attractive package: In return for Rhee's compliance with an armistice, and retention of the ROK Army within the U.N. Command, the United States would build up the South Korean Army to 20 divisions and provide the equivalent of $1 billion for rehabilitating South Korea. Rhee rejected the offer out of hand, saying: "Your threats have no effect upon me. We want to live. We want to survive. We will decide our own fate."

Rhee had another trump card to play, and he did, much to the chagrin of the United States and the U.N. Command. Since ROK troops manned two-thirds of the front, a sudden decision to remove them from the U.N. Command would be a nightmare. Rhee hinted he might even ignore an armistice and continue to fight. But, it turned out, Rhee ordered ROK guards to release 27,000 nonrepatriates from their compounds, hoping that his POW release would create such turmoil and recriminations at Panmunjom that the truce talks would be broken off indefinitely. The whole incident was an open gesture of defiance which publicly flouted General Mark W. Clark's authority and demonstrated that Rhee's wishes could be ignored only at the peril of his allies. Since the Articles of Armistice had already been finalized, Rhee's prisoner release was a bombshell. The communists raised questions about the U.N. Command's ability to control Rhee and the ROK government. But the communists were so eager to have a truce, even with the division of Korea reaffirmed, that they contented themselves with ritual denunciations of Rhee and the U.N. Command. The U.N. was so eager to have a truce that it joined the enemy in denouncing Rhee's action, and both sides agreed that the armistice talks would continue. The most extreme action Rhee could devise to prevent the continued division of his nation had failed. But neither his own people nor the governments of the world could doubt that he had done his best, short of military adventurism, to avert an armistice. On July 10, 1953, the truce talks resumed. The last act in this tragic drama of war was ready to unfold.

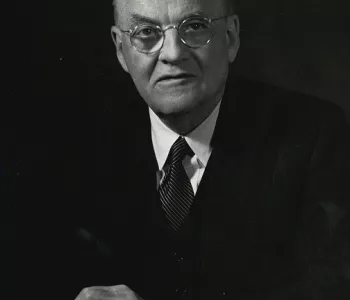

Infuriated by Rhee's "stab in the back," as Clark called it, Washington dispatched Assistant Secretary of State Walter Robertson to Seoul to persuade Rhee to accept an armistice. For more than two weeks, Rhee and Robertson held bargaining sessions almost daily. Finally, on July 12, Robertson flew to Tokyo with a letter from Rhee to President Dwight D. Eisenhower agreeing not to obstruct an Armistice. Rhee's letter to Eisenhower agreeing to a cease-fire was his only substantive concession. In return, Rhee obtained the promise of an ROK-U.S. mutual security treaty, a lump-sum payment of $200 million as the first installment of a long-term economic aid program and expansion of the ROK Army to 20 divisions.

The War Ends

On July 27, 1953, one of the 20th century's most vicious and frustrating wars came to a close with the signing of an Armistice at Panmunjom. The signing on Aug. 8, 1953, of a mutual security treaty between the ROK and the United States was the culmination of a lifelong ambition, an event which allowed a bitter 78-year-old man to recall with some satisfaction how, nearly fifty years before, he had traveled to the United States to plead in vain for American protection against the Japanese. Rhee made the signing the occasion for a discourse on Korean history: "Korea has been considered as a weak, minor country, helplessly situated among powerful nations and yet rich in natural resources, thereby attracting many an aggressive power to covet the land. Throughout history Korea has been regarded as a no-man's land whose independence, neighboring powers assumed, is unavoidably dependent on one of the big powers…. Following Japan's failure to conquer the whole world, the Allied nations brought up a decision made by themselves which finally caused the tragic division of Korea, north and south. Nevertheless, the united effort of our people, the patriotism of our youth, and the assistance from friendly nations all contributed to developing our armed forces. Now that a defense treaty has been signed between Korea and the United States, our posterity will enjoy the benefits accruing from the treaty for generations to come."